Council Housing in Stockton’s Future

SUMMARY

This submission will address the scale of housing need in Stockton-on-Tees. It is the view of Housing Action Teesside that the scale of Stockton’s housing challenges can only be addressed sustainably in the long term through the reintroduction of local authority-owned, democratically accountable council housing stock, eventually built on a large scale.

This submission will cover the extent of housing need in Stockton, summarise the history and context of social housing in the UK, the resumption in council housing in other parts of the UK today, and the barriers and next steps if Stockton Borough Council was to begin building council housing again.

HOUSING ACTION TEESSIDE

Housing Action Teesside is a tenants’ union and housing campaign representing hundreds of tenants across Teesside, in both social and private rented housing. Our organisation is united around the belief that the housing crisis was created by political choices over many decades which put private profit ahead of people’s needs, and the commitment to organise alongside our neighbours for real change in our community to fight housing injustice.

As a group, we support individual tenants with housing issues and campaign collectively to improve housing conditions.

Many of our members are trapped in desperate housing conditions or have been on housing waiting lists for years. Other members, including vulnerable people, are forced into exploitative private rented housing they cannot afford leaving them in a cycle of homelessness, because there is no possibility for them to access social housing. We have come to the conclusion that solving the housing crisis in Teesside and across the country requires large-scale council housing-building.

HOUSING NEED IN STOCKTON

Housing affordability

Although housing in Stockton-on-Tees, along with the rest of the North East of England, is generally less unaffordable than elsewhere in the country, dramatically rising housing costs across the country over the last three decades have been affecting Stockton as well.

Housing in Stockton today is 85% less affordable than it was in 1998 (as calculated by the ratio of house prices to median workplace earnings, Office for National Statistics). The private rented sector, which includes many former council homes sold under Right to Buy, is seeing even faster increases. Average monthly rents in Stockton today are £649, which increased by 7.9% since July 2023 (higher than the 6.1% rise across the North East). The highest rent increases were in one bed properties, with average private rents rising by 8.4% in a single year. Of course, these average rent statistics mask the fact that some private tenants saw small or non-existent rent rises, while others have seen dramatic increases in their rent which have placed them in significant hardship.

Homelessness

As many residents are priced out by growing housing unaffordability, increased housing costs alongside the broader cost of living crisis is forcing growing numbers into homelessness.

The number of households seeking homelessness support in Stockton in March 2024 was 9.6% higher than in March 2023, and 82.7% higher than in 2019. Of the 833 households assessed by Stockton Council in January-March 2024, 526 were assessed as being owed some form of homelessness support under the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017, but only 191 were owed the “relief duty” meaning that the council had to help them secure accommodation.

Of those who were not accommodated, many were not considered “priority need” or could not establish a strong enough local connection, or could not be confirmed to be homeless due to their private landlords being uncontactable (so they would be advised by council housing officers to sleep rough on the streets until outreach teams spotted them). Many have given up on hope of finding permanent accommodation and have been left in cycles of sofa surfing or sleeping rough.

The increasing scale of need, and limited temporary accommodation available, is placing pressure on many local authorities to deny more applicants the “relief duty”. While in April-June 33% of initial homelessness assessments in Stockton resulted in the “relief duty” being applied and an offer of accommodation, this fell by January-March 2023 to 29% and has fallen again in January-March 2024 to 23%. More people experiencing homelessness in Stockton are being left in substandard accommodation, or forced to sofa-surf, sleep rough or squat.

For those left in private rented accommodation, rent rises and the continuing use of Section 21 (no fault) evictions makes their lives constantly insecure. Section 21 evictions in January-March 2024 were at 138% higher than in 2019. In the last year Section 21 evictions have risen by 38%.

Social housing waiting lists, including both those currently homeless and those in inappropriate private accommodation who are seeking a social tenancy, are continuing to grow. Shelter estimates that in 2023 1,921 people in Stockton were on social housing waiting lists.

Experiences of tenants

Housing Action Teesside members in both private and social rented accommodation are living through often extreme housing disrepair, and the frustration of being trapped on waiting lists.

A 2022 survey of Housing Action Teesside members in Thirteen social rented housing found that 73% of respondents experienced problems getting repairs done, with common problems including damp, mould, broken windows and doors, and broken boilers. Tenants experienced impacts on mental and physical health, being unable to use utilities such as showers or washing machines for months, and lost income from waiting in for workmen who never arrived. 57% had been unaware of Thirteen’s complaints process.

Of these, prominent problems include damp and mould. One Housing Action Teesside member and Thirteen tenant in Billingham was left for years in housing with growing problems with black mould (see picture below), and when Thirteen recognised that her housing was unlivable, the only alternative accommodation that Thirteen offered was inappropriate for her due to her disability.

Another Housing Action Teesside member was on housing waiting lists for four years in substandard accommodation. Due to her and her adult daughter having developed disabilities they were unable to access the entire top floor of her house, so both were forced to sleep on a cramped sofa-bed in the living room. While they were supported to create a housing profile on Tees Valley Home Finder, their proof of identity documents were repeatedly deleted from the website due to technical issues so their priority banding was lost at least four times. For clients trapped on waiting lists who do not have the IT technical skills to constantly check and update their Tees Valley Home Finder or My Thirteen profiles, or are preventing from doing so due to a disability, there can often be no realistic prospect of successfully bidding for housing.

The lack of available social housing stock therefore prevents social landlords from being able to provide alternative accommodation while work is being done, as well as trapping people on housing waiting lists and in cycles of homelessness.

SOCIAL HOUSING – HISTORY AND CONTEXT

Postwar housebuilding

The UK as a whole is facing a significant shortage of social housing. Only 6,000 homes for social rent are built each year, while waiting lists according to Shelter are at roughly 1.3 million.

Historically the UK, facing substandard housing and high waiting lists in difficult economic circumstances, has used council house-building on a massive scale as a means to stimulate the economy and relieve housing need. Between 1946 and 1951 1.2 million new homes were built, of which 80% were council houses. Overall up until 1980, England built social homes at a rate of 126,000 a year, the vast majority of which were council housing.

Privatisation of social housing

The introduction of Right to Buy and the virtual elimination of grant funding of council housing under the Thatcher Government led to a major reduction in the supply of council housing. Demolition of ageing stock and sell-offs of council housing under Right to Buy continued to reduce the social housing supply. This continued under the 1997-2010 Labour Government with the further loss of 655,000 social homes.

Furthermore, the nature of social housing was transformed by the introduction of private housing associations. The lack of funding for local authorities led to a growing repair backlog. In order to be given funding for repairs to bring homes up to the Decent Homes Standard, tenants were given a one-off opportunity to vote for stock transfers from their local council into a private housing association.

Although this led to short-term funding and an improvement in housing conditions, this was the kind of trick that could only be played once; by leaving housing stock in the hands of corporate social landlords, who are not democratically accountable to their residents and who receive funds not from government grants but from the corporate bond market, there is now limited incentive for housing associations to improve their properties or build new social housing. Now, decades later, our members in social housing feel that their landlord’s “social purpose” has been forgotten, and social housing waiting lists continue to grow.

Today, building of social housing is negligible compared to housing need. Nationally, councils spent £2.3 billion on temporary accommodation between April 2023 and March 2024. This increased by 29% in last year, and represents a 97% increase in the last 5 years. Between 2021 and 2026 it is projected that £70 billion in public money will be paid to private landlords in housing benefit, whereas only £11.5 billion will be paid out by central government in capital grant for affordable homes in that period.

Current social housing in Stockton

The dominant housing association in Stockton is Thirteen Housing Group, which is a Teesside-based housing association, which owns and manages 34,000 properties. Thirteen was created through an amalgamation of other social housing providers. The history of Thirteen is a complicated one. Firstly, Stockton Borough Council set up Tristar Homes as an ‘arm’s length’ company in 2002 to manage council housing stock having received a 2 ½ star rating. Unfortunately, it then went on to receive a 1 star with no chance of improvement from the regulators.

Meanwhile in Hartlepool, the housing stock was transferred from the council to Housing Hartlepool in March 2004. Tristar Homes went on to take ownership of the council’s stock in 2010, joining Housing Hartlepool in a partnership to form Vela.

In Middlesbrough, Erimus Housing was created from the transfer of council housing stock in November 2004. Four years later, Fabrick Housing Group was created by the joining of Tees Valley Housing, a traditional housing association, and Erimus Housing.

Thirteen Group was formed when in 2014 Fabrick and Vela amalgamated to form one group with four landlords. In the first year alone, Thirteen Group saved £7.5m and consolidated in 2017 to become one landlord as Thirteen, to bring “even further strength and a simpler, easier business to work with”. Gus Robinson Developments was purchased in 2018 to help play a part in building houses within the North of England for Thirteen. Thirteen now manage some 34,000 homes across the North East region, spanning North Tyneside to York, with the majority of properties (30,000) in the Tees Valley.

Thirteen offers homes for market sale, in addition to those rented at affordable (80% of market rents) or with social tenures.

According to Thirteen’s most recent annual report in 2023, Thirteen’s total reserves are increasing year-on-year due to high current operating surpluses. Thirteen’s total reserves increased from £630 million (2021) to £695 million (2022), and have as of March 2023 reached £786.6 million.

COUNCIL HOUSING IS THE ANSWER

The long-term arguments for building social housing, and in particular council housing, are clearcut. By building council housing Stockton could relieve the housing waiting list, allow it to move vulnerable people on from temporary accommodation, and provide a realistic alternative to private rented housing which would provide a downward pressure on private rents.

Hyde’s Value of a Social Tenancy open-source methodology estimates that an average new social tenancy provides £16,906 per year in benefits to public finances (including rent, as well as increased employment from construction and maintenance activity). Moreover according to National Audit Office modelling (The Affordable Homes Programme since 2015, 8 September 2022), building housing for social rent creates 3.4 times more economic benefit than it costs. This includes benefits in preventing rough sleeping and homelessness, reducing the cost of housing benefit, relieving financial stress and insecurity, and enabling workers and families to live in appropriate housing closer to support networks and resources.

Council housing, due to local authority democratic accountability and statutory duties, is uniquely able to tie in social housing with broader planning and social care duties.

Of course, Housing Action Teesside recognises that this problem could not be solved from a standing start, and acquiring council housing poses its own challenges. Nevertheless we argue that Stockton Borough Council should begin acquiring council housing today at a manageable scale, and plan for a future in which large-scale council house-building can end the housing crisis.

Council housing today

Other local authorities are ahead of Stockton in seeking to begin replenishing their council housing stock. While some local authorities such as Stockton have transferred all of their council housing to housing associations, many continue to own and build council housing. 158 out of 294 councils in England today have Housing Revenue Accounts, indicating they have more than 200 council-owned properties.

In addition, since the abolition of the borrowing cap on councils’ Housing Revenue Accounts in 2018, many councils have begun building council housing again. Last year, 9,054 homes were built by councils directly, and an additional 3,049 homes were built by council-owned housing companies. This is nowhere near the scale required, but it is a crucial start.

Locally, several local authorities are pursuing projects to build council housing. Durham County Council, which previously disposed of its housing stock to Believe Housing, has now announced it is seeking to build 500 new council homes again. Hartlepool Borough Council reopened its Housing Revenue Account in 2016 and now owns roughly 300 properties, and is exploring a new scheme of 75 new council homes. North Yorkshire Council’s housing strategy through 2029 has the delivery of 500 council homes as a “minimum baseline”. Darlington’s social housing stock continues to be council-owned, and it has reported it has designed and built 400 homes in-house under its current housing plan.

It is important that Stockton not be left behind by this process, which could potentially lead to housing unaffordability and waiting lists in Stockton outstripping neighbouring local authorities.

Starting from scratch

Some additional challenges are presented by seeking to acquire council housing without any existing stock. However these are not insurmountable.

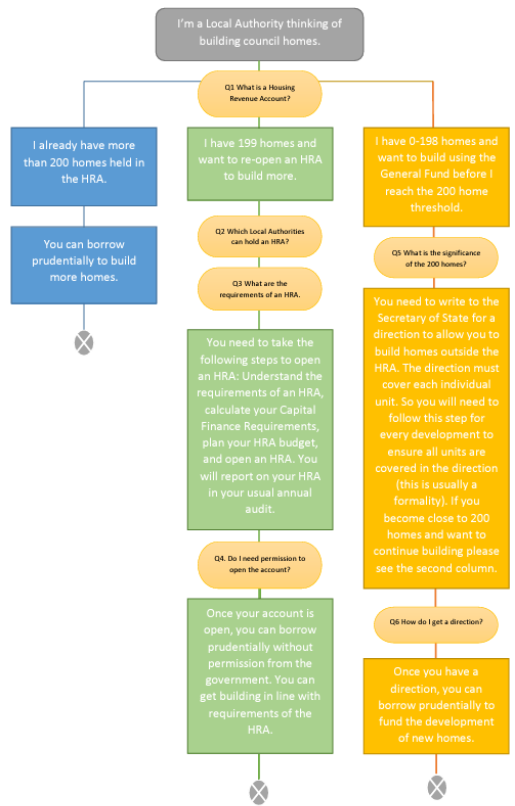

As it has no existing housing stock, Stockton Borough Council currently has no “Housing Revenue Account”. Housing Revenue Accounts (HRAs) are landlord accounts by local housing authorities acting as landlords of council housing under Part II of the Housing Act 1985. HRAs ring-fence certain defined transactions within the General Fund, for example including management and maintenance, major repairs, loan charges and depreciation costs. They receive incomes in the form of rents and service charges.

However, even without an HRA, local authorities are still able to acquire up to 200 council homes using their General Fund. Once a council acquire 200 homes, it would need to set up an HRA. Any use of the General Fund for acquiring council would require approval in the form of a “Direction” from the Secretary of State (Angela Rayner) – though as we have seen, these are being approved in many local authorities across the country.

Any borrowing to fund house-building would need to be permitted by the Public Works Loan Board at the Treasury. Local authorities are able to borrow for council house-building against their expected rental income, in line with the Prudential Code.

The process for setting up a Housing Revenue Account (HRA) is for local authorities to write to the Secretary of State stating that the local authority is establishing an HRA.

See below for a summary of the process:

(Source: Labour Campaign for Council Housing)

Addressing concerns about council housing

There are additional costs associated with controlling housing stock, such as the requirement to maintain and administrate. Many skills were lost when Stockton Council transferred its housing stock to private housing associations. However many local authorities have arrangements with adjoining local authorities (such as for example Hartlepool, Durham or Darlington) which would allow for the existing housing authority to carry out maintenance for the new council housing. This cooperation with neighbouring authorities would allow Stockton to begin building council housing, and develop its own skills and infrastructure required to manage its own stock over time.

Building housing does have its own challenges, such as acquiring land. However Stockton Council currently has major developments ongoing (in Stockton Town Centre and in Billingham) which will likely include housing, and in which the Council could seek to include some council housing in the developments. Furthermore, many local authorities avoid the cost of building by first prioritising buying ex-council properties. Action on Empty Homes have found that more than 50,000 long-term empty homes are in the North East of England alone, and many of these could be bought by Stockton Borough Council to put into immediate use as council housing.

One significant concern which is regularly raised is Right to Buy. This does pose a challenge to any local authorities seeking to build council housing, as if tenants exercise Right to Buy it could represent a net loss for the council. However, it is expected in the long-term that Right to Buy will likely be reviewed, including potentially changes to the discount rate, which could make building large-scale council housing more financially sustainable. It may therefore be in Stockton Borough Council’s interests to begin building council housing at a limited scale now, and seek to expand this in the future when national regulations change.

CONCLUSION

Our members and other residents across Stockton are experiencing a housing crisis, and need ambition and urgent action from the Council. In the long-term, Stockton’s housing sector will not be sustainable without large-scale council housing. We urge Stockton Borough Council not to be left behind, and to take the steps now to begin rebuilding Stockton’s social housing under direct, democratically accountable council control.